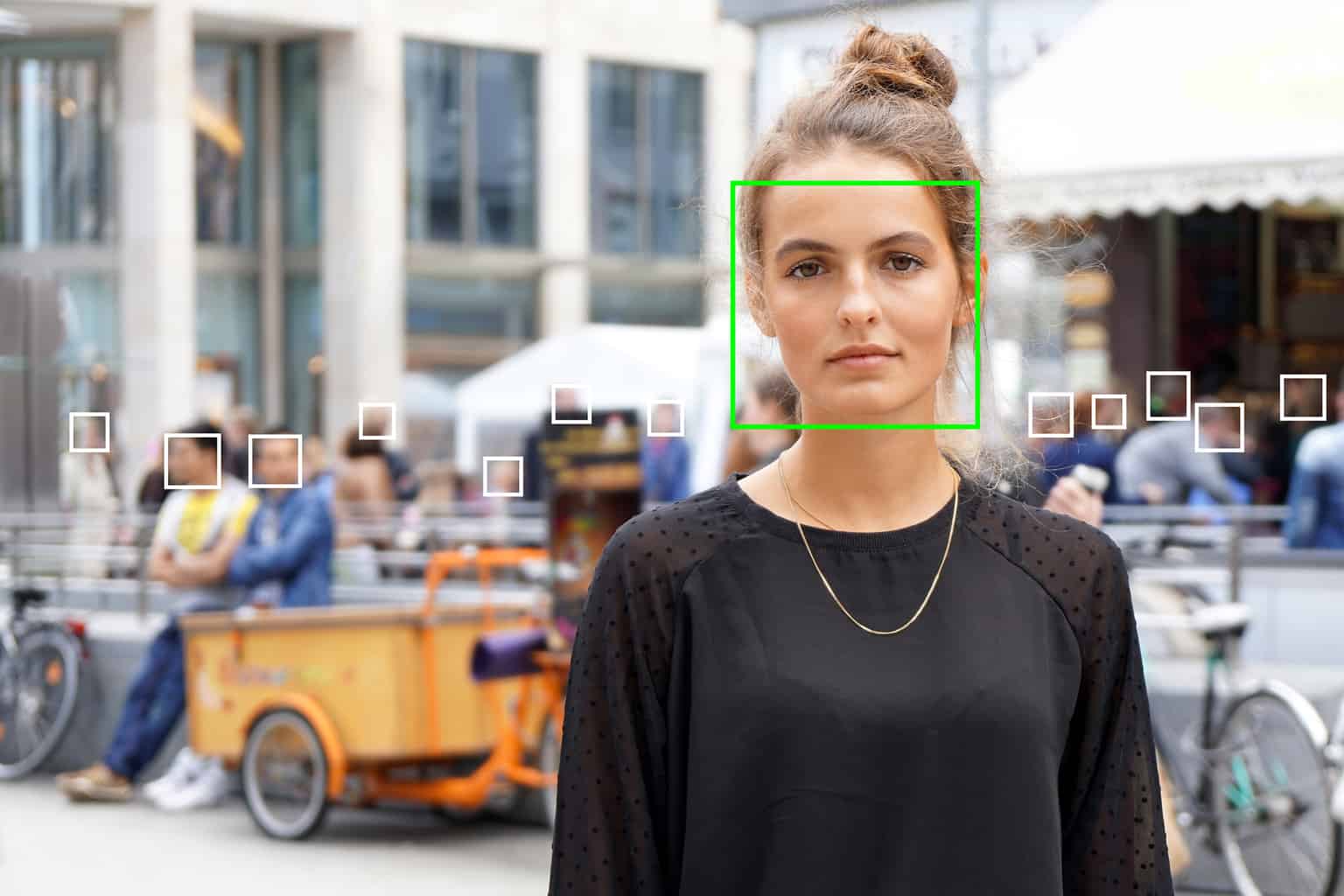

What if, in the future, facial recognition was used in our towns ?

6 minutes of reading

What if, in the future, facial recognition technologies went into general use in our towns and buildings? In China where this is already happening, the increasing use of such technology in both public and private spaces raises the spectre of mass surveillance and the risk of new attacks on privacy. While the number of experiments is increasing around the world and certain American towns are already taking the lead in preventing its use, the debate is beginning to take shape in Europe.

“The challenges of data protection and risks of attacks on individual liberties that such systems are liable to lead to are considerable including the freedom to come and go anonymously.” It is in these terms and in a report calling for a “debate which is up to the challenges” that the CNIL (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés) raised the alert at the end of 2019 against “red lines which must not be crossed”, including in the experimental use of the technology. The tone was set and sets the position of the French gendarmes on privacy, following their opposition to experimenting with facial recognitions systems in two colleges in the south of France.

The technology is being developed in a number of urban components

The stop put on the use of the technology in educational establishments does not prevent its development in many other urban components characterised by significant pedestrian flows: public spaces, transit locations such as stations and airports, public transport, stadia. There are many examples of these in France. Since June 2018, the Parafe automated passage system at the outer barriers of Orly and Roissy airports has incorporated facial recognition technology which could gradually replace the existing system operating with a fingerprint sensor. At Metz, football club supporters angrily discovered at the start of 2020 that a system to detect “persons forbidden from entering the stadium” was being tested. During the last Nice Carnival, the Town tested the efficiency of the technology by simulating a number of scenarios (finding a lost child in the crowd, finding a fugitive, etc.). The Town of Nice, particularly active in rolling out the technology does not hide its ambition to use it for security and safety reasons. From June 2018 it hosted an experiment for an innovative project on the “Safe City” led by a vast industrial consortium headed by Thales which aims to test technological solutions and consider the changes to national legislation in this regard. In this context, a test project for emotion recognition and analysis software to detect suspect behaviours on the tramway caused an outcry at the start of 2019.A rollout supported by economic prospects

The list is long and could extend to other actors. Certain hospitals for example envisage using the technology to control access to certain areas in their establishments or locate certain types of patient (children, Alzheimers’ patients) within their building. Besides the facilities which facial recognition technology can provide, the French fever for experimentation is also fed by prospects of cost rationalisation (by administrative simplification or availability of remote services for example) and the desire to be competitive in a market which appears profitable and on which a number of industrial companies have positioned themselves. Which was summed up as follows (quoted by the journalist Olivier Tesquet, specialist in surveillance mechanisms) by Reneau Vedel, when he was in charge of digital prospects at the Interior Ministry before taking up his functions in March 2020 as coordinator of the national strategy for artificial intelligence: “We must agree to find a balance between uses for the purposes of governance and measures to protect our freedoms. As otherwise, the technology will be matured abroad and our industrialists, although world leaders, will lose this race”.Attempts at supervision to preserve individual freedoms

To maintain this balance, the GDPR (General Data Protection Rules), which came into force in May 2018 and governs all procedures associated with personal data, is on the front line. But facial recognition seems to move the goalposts as the GDPR theoretically prohibits the use of this technology: it lays down a principle prohibiting the processing of sensitive data, a category under which the biometric data used by this technology is classified. There are actually numerous exceptions, in particular the case where the explicit consent of the individuals concerned is obtained or for cases of major public interest. In parallel any project using facial recognition technology must undergo an impact analysis with regard to data protection (APID).Resistance from towns and civil society

The level of supervision of the use of the technology is a red herring for civil liberties defence associations who denounce the highly intrusive nature of the technology, and for some who call for an outright ban pure and simple. This is the case with the Quadrature du Net who think that “There can be no ethical facial recognition or carefully considered use of biometric surveillance” and considers facial recognition as “a technology which is exceptionally intrusive, dehumanising and ultimately designed for the surveillance and permanent control of the public space”. For the association, the systems used for authentication (certifying the identity of a subject), although less invasive, are as much to be banned as those aiming to carry out identification (recognising and identifying one subject from another) as they help to make use of the technology more commonplace. The source of a number of actions against current experiments, the association has also launched the platform Technopolice which lists and documents experiments which move in the direction of surveillance of an urban space for security purposes. The same scenario is playing out in the US where the American Civil Liberties Union, a powerful association defending individual liberties, has lodged a complaint against the American government demanding greater transparency on the use of the technology as part of its recent expansion in airports. But in the country, mobilisation extends beyond civil society to the regions which are taking the lead. In May 2019, San Francisco became the first US city to ban the use of facial recognition by the police and government agencies. A few months later, the State of California legislated to prohibit its use on the cameras of its police officers. For Olivier Tesquet, the increase in ethical and philosophical questions and the alerts raised against potential drifts reveal an increasing mistrust of digital technology, indeed a “digital disenchantment” which takes precedence over its liberating potential. With regard to facial recognition, the author of the essay “A la trace” regrets that this tool which is widely used in authoritarian regimes is subject to such a limited debate in liberal democracies. The dissenting movements also question the reliability of the technology, its costs and risks of malfunction. A study carried out by researchers at the University of Essex and published in 2019 has revealed faults in the software used by the metropolitan police in London noting an error rate of 81%.Large-scale facial recognition in China: where reality catches up with the dystopias

China seems far removed from these questions and is advancing in giant steps in rolling out the technology. There are an immense number of uses which show just how much the technology has entered every aspect of daily life, including private life: in Beijing, a number of council houses have been fitted with facial recognition locks to combat illegal subletting and block access to the blocks by individuals who cannot be identified as tenants or their families. More recently, the epidemiological context of the coronavirus has shed light on the large scale data analysis systems used to track patients and stem the epidemic. In the country, facial recognition combined with videosurveillance constitutes the bases of the social credit model put in place by the authorities, a highly controversial project which aims to carry out surveillance of citizens on a massive scale to install a system of rewards and penalties according to their behaviours. Across the world, paths diverge and testify to radically different approaches in the use of this technology. Could there be a third way, between prohibition and unrestricted usage of the technology whereby facial recognition would be limited to functions which could make a truly positive difference to the daily lives of ordinary people and remove its use for security and surveillance purposes?More reading

Read also

What lies ahead? 7 megatrends and their influence on construction, real estate and urban development

Article

20 minutes of reading