The return of eco-materials

In October 2018, the IPCC report recommended replacing concrete, steel and aluminium with eco-materials in order to give us one more chance to remain under the 2 °C global warming limit—or if possible, the 1.5 °C limit—and comply with the Paris Climate Agreement.

“Eco-material”, a common term since the 1990s, entered the French dictionary in 2019, where it is defined as a “construction material whose use respects the environment”. It includes stone and raw earth (geosourced, mineral-based materials), as well as wood, straw, hemp and reeds (biosourced materials that come from plants or animals). For the construction industry, which is responsible for one third of domestic greenhouse gas emissions, according to a June 2019 study by ADEME and Carbone 4, these natural materials are a major source of interest. Extracting, harvesting or sawing these materials requires relatively little energy, and they can be recycled, reused and processed with a lower environmental impact than other materials. Their lifespan is counted in centuries: even the straw used in Feuillette House, which was built in Montargis, Loiret in 1920, still maintains its original properties. And to top it all off, some geosourced or biosourced materials have excellent thermal properties in terms of insulation and heat capacity.

The 2020 Environmental Regulation (RE 2020), which enters into effect in summer 2021, “should make the use of wood and biosourced materials”, which are capable of storing carbon, “almost systematic by 2030, including for individual homes and small apartment buildings”, according to the press pack issued by the Ministry for the Ecological Transition. This process should reduce buildings’ carbon footprints throughout their lifecycles, from construction to demolition, while also ensuring comfort during winter and intense heat.

“At the same time, a government label will allow public or private contracting authorities to anticipate the future requirements of RE 2020, set an example, and serve as a prelude to future buildings farther down the line.”

These measures will trigger a radical shift in building types and construction methods, “which will require site workers and tradesmen to alter their practices and undergo training. This is particularly true when it comes to using wood and biosourced materials, which will substantially change how construction sites are designed, supplied and managed.”

However, a quarter of the country’s 2050 housing stock has not yet been built, according to projections released by the Ministry for the Ecological Transition (to address concerns raised by the decrease in household size and demographic growth), and multiple long-term economic issues have arisen.

First, the need to supply eco-builders with eco-materials. There will be no shortage of earth, straw, hemp and reeds, according to their respective industries. However, the country’s 500 stone quarries cannot be endlessly tapped, and there are serious threats to forests, according to the April 2020 report from the Court of Auditors (Developing the Forest-Timber Industry, Its Economic and Environmental Performance). These threats include climate disruption, an excess number of large game animals (which impede forest replenishment), and unfavourable opinions toward hunting and logging.

This restructuring of the forest-timber industry, which is running a deficit due to log exports (particularly to China) and imports of processed products such as CLT, is vital: “France has one of the largest forests in Europe, but imports wood for construction—that means there’s a problem! We have to reorganise the industry. It will create many more jobs”, tweeted French President Emmanuel Macron in April 2018. Only ambitious public action will enable this reorganisation, notes the Court of Auditors. These recommendations—a new environmental regulation, substantial financial assistance—have been followed. On 22 December, Julien Denormandie, the Minister of Agriculture, announced a 200-million-euro relief package to replant 50 million trees in the country’s forests. On 16 December 2020, BPI France launched a 70-million-euro Wood and Eco-Materials Fund to prop up the industry. The ball is in their court.

A few companies and projects that are earning buzz

The foundations for tomorrow’s buildings have already been laid. Often compared to the homes of the three little pigs, a number of straw, wood and brick buildings from major construction companies and fledgling developers, like REI Habitat and Woodeum, are making headlines. Having earned E+C- labels (for positive-energy and carbon-reduction buildings), these innovative structures, inspired by the past, helped push through the 2020 Environmental Regulation bill, even before they were subject to its rules. They have “set an example and serve as a prelude to future buildings farther down the line”, to borrow the words of Emmanuelle Wargon, Minister Delegate for Housing to the Ministry for the Ecological Transition—and for good reason.

MATERIALS TRACEABILITY

Using eco-materials and working as much as possible with whatever is on hand or underfoot represents a revival of common-sense practices that were already recommended two centuries ago by Léon de Perthuis, in his Treatise on Rural Architecture: “If the locality did not present (…) any construction-worthy stones, [the owner] would be forced to employ in his constructions either wood, fired brick, mud brick or rammed clay, according to the nature of the available lands. And so, after surveying the local resources, he would assign, in proportion to the elevation required for the walls of each building, the variety of fabricated materials most economical and at the same time most suitable for the degree of solidity its purposed demanded.”

The public delights in reading about the origin of the ashlar used in the Le Metropolitan project (a group of 283 homes under development by Verrecchia Construction in Rosny-sous-Bois, Seine-Saint-Denis): the Saint-Maximin quarry in the Île-de-France region.

They enjoy learning that in order to complete a project in Confluence, Lyon (a 1,000 m2, three-story building designed for Ogic by architecture firms Clément Vergély and Diener & Diener, which was made with rammed clay—a traditional technique from the Rhône-Alpes region), Nicolas Meunier’s team used earth from an excavation site less than 20 km away. They are pleased to discover that the earth used to build La Maison des Plantes de Ricola in Basel, Switzerland—the largest rammed-earth building in Europe (at 110 m long, 29 m wide and 11 m high, it was designed by Herzog and de Meuron and built by Lehm Ton Erde de Martin Rauch)—partially comes from the site itself, and from a quarry 10 km away. And they take comfort in knowing that if these buildings were ever destroyed, they would return to the earth they came from.

As part of the same circular economy process, excavated material from the future Grand Paris Express site will be used to build an entire raw-earth neighbourhood by 2030 in Ivy, Val-de-Marne, on the site of the former Paris waterworks plant. The material will be converted into bricks at a factory created two years ago in Sevran, and will then be used to build earthen, stilt homes over a tract of water. The chief architect of this project, dubbed Manufacture-sur-Seine, is none other than Wang Shu, winner of the Pritzker Prize in 2012.

The builders have pledged to use traceable materials, as in the restaurant industry. “For each stud, each floorboard, we can tell you who the manufacturer is, and which massif it comes from”, promised Paul Jarquin, Chairman and CEO of REI Habitat, during his presentation on L’Hester, a property-development project that delivered a twenty-unit, “locally sourced” apartment building in early 2020. The builders also pledged to indicate which forests the wood (primarily spruce) came from: the Grand-Ouest region, Massif Central, Jura or the Savoie Massif.

Working with local materials whenever possible, and with local partners, is also the goal of Bouygues Bâtiment France Europe. The company has contracted several regional companies to build the headquarters of Podeliha, a social housing provider in Angers. These include Piveteau Bois, a company based in Vendée that specialises in making CLT panels, and Caillaud Bois, a family-owned company based in Chemillé-en-Anjou, which will lay the panels and manufacture and install the framework, studs and beams.

NATURAL ARCHITECTURE AND WELL-BEING

The return to using local materials and local partners has created a boom in the natural architecture prized by Kengo Kuma—a happy marriage between architecture and location, where buildings are imbued with a “natural” feeling.

In the countryside, Jean-François Daures’ green school complex in Montpezat-sous-Bauzon, near Aubenas, which was delivered in 2014 and won the Sustainable Construction Grand Prize at the Green Solution Awards in 2019, is in perfect harmony with the surrounding scenery. Vegetation is everywhere: in the Douglas-fir superstructures, sourced from the Cévennes region, as well as the roofing, the cladding and the scenery. Even the road that runs by the school has been decorated with greenery. The idea, according to the architect, was to “pull the prairie green over the school complex, covering it in a plant canopy”, and to showcase local biodiversity. The teachers have all noticed a marked improvement in their student’s well-being, as well as an increase in academic performance.

In Aerem’s straw and wood factory in southern France, delivered in 2018 by the Toulouse-based firm Seuil Architecture, the workers say it’s easy to forget about the winter and poor weather, which are more noticeable in concrete buildings. “Multiple studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of a wood environment on the health and well-being of its occupants”, reported Angers Hospital, in an article in La Dépêche on 2 May 2019. “However, few hospitals use wood due to its porous surface, which is seen as unsuitable in environments vulnerable to microbial infections. This may require cleaning or lead to cross-contamination, hospital-acquired infections, etc.” However, in Canada, studies show that cancer patients recover more quickly in such an environment.

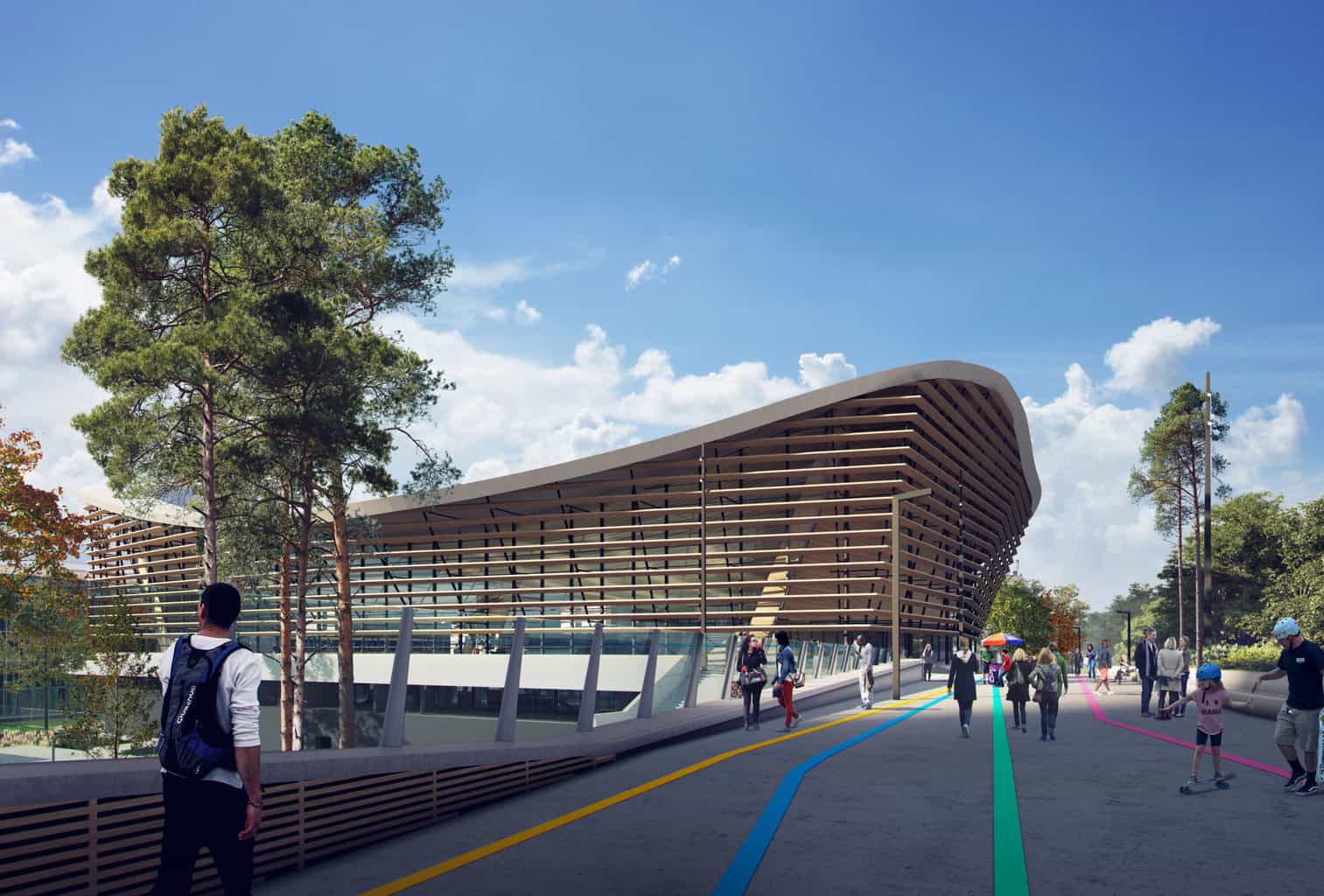

(Français) Conçue comme « un écrin de bois suspendu au ciel » pour la Métropole du Grand Paris, la structure du centre aquatique de Saint-Denis sera principalement en bois. Le chantier, confié à Bouygues Bâtiment Ile-de-France, qui inclut également un franchissement pour Bouygues Travaux Publics, devrait débuter à l’été 2021 et s’achever fin 2023. Le centre aquatique accueillera les épreuves de waterpolo, plongeon et natation artistique lors des Jeux de 2024. Architecture VenhoevenCS & Ateliers 2/3/4/ - Image : Proloog

FEATS OF ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN PLANNING

Using eco-materials doesn’t rule out bold architectural styles. Wood, which is five times lighter than concrete, allows for construction in the French capital, which is already highly dense, as well as in underground car parks. The material is also being used by Woodeum to build a three-building residence hall for students and young athletes over the Paris ring road at Porte Brancion, and was also used to add five floors to a supermarket at Place de la Nation.

But what the press is celebrating most of all is “the tallest wooden building ever constructed”. Mjøstårnet, in Brumunddal, Norway, currently holds the record with 85.4 metres over 18 storeys. In France, the Hyperion residential tower block (57 metres tall, 17 storeys), which is under construction in Euratlantique, Bordeaux, will be completed in May 2021. Developed by Eiffage Immobilier, the building is set to dethrone the current tallest wooden tower (38 metres) at the “Sensations” building complex in Port du Rhin, Strasbourg, which was delivered by Bouygues Bâtiment Nord-Est in 2019.

French architecture firm Rescubika Creations has proposed building a 160-storey wooden skyscraper, dubbed Mandragore, on Roosevelt Island in east Manhattan, but for now it remains just an aspiration.

Industry structuring

The growing appeal of new techniques since the end of the 19th century—including concrete and steel—as well as the wartime loss of manpower and expertise passed down from prior generations, have weakened the wood, straw and stone industries since the 1960s. However, these industries are still in the picture, and the new environmental regulation (RE 2020), which is designed to reduce buildings’ carbon footprints by encouraging the use of biosourced materials, should pick up their burgeoning momentum once it is implemented in summer 2021.

MAIN INDUSTRIES

Straw is an abundant resource in France, with 10% of its annual production capable of insulating every building, according to the French Straw Construction Network (RFCP), and the straw industry itself is the most dynamic in Europe, with 500 annual builds and a growing number of buildings insulated. The hemp industry, whose top European producer is France, is in a similar position. Nothing on the plant is wasted: the fibre (husk) is used as insulation, and the shives (the woody centre of the stalk) are used to make coatings and vegetal concrete for renovations and new builds. Stone, for its part, still boasts 715 specialised companies and 4,000 direct jobs, with revenues of 515 million euros, according to figures from the natural stone industry. Lastly, raw earth, which is promoted by the CRAterre association, will be the subject of a “national project” currently under development by the Ministry for the Ecological Transition.

The forest-timber industry carries the most weight. According to the April 2020 report from the Court of Auditors (Developing the Forest-Timber Industry, Its Economic and Environmental Performance), the sector accounts for 440,000 jobs (compared to 1,200,000 in Germany) and 60 billion euros: 20 billion upstream (logging) and 40 billion downstream (the wood processing industry, including real estate developers, sawmills, carpenters, joiners, energy engineers, papermakers, etc.)

PARADOXES OF THE FOREST-TIMBER INDUSTRY

However, the industry in France is characterised by a series of paradoxes that are impeding its development, according to the report from the Court of Auditors.

France has been unaffected by deforestation: its forests have doubled in size over two centuries, due to the spontaneous afforestation of abandoned agricultural land. They cover one third of the country, and constitute one of the largest forest areas in the European Union, after Sweden, Finland and Spain. However, only half of its annual growth is harvested, and it is poorly integrated between the upstream and downstream ends of the industry, between supply and demand: it exports less rough timber than it imports processed products, leading to a substantial, seven-million-euro trade deficit, which widened by 4% between 2018 and 2019, according to an August 2019 report by Agreste Infos Rapides (Wood and Wood By-Products). With a forest area 45% smaller than that of France, Germany’s lumber production is almost three times higher (23 billion m3 vs France’s 8 billion m3); Austria also exceeds France, with 9.6 billion m3 of lumber. With a production capacity higher than that of France, and markedly more competitive prices, foreign competition is growing. Only seven French companies make Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT), which is commonly used in the construction of wood buildings, despite it having been invented in France in the late 1940s.

Additionally, although forests are growing, they are not regenerating quickly enough, either naturally or through planting: large game, the hunting of which is heavily regulated, have multiplied over the last forty years (deer and roe deer by eleven, boars by twenty), eating or trampling on seedlings and stripping the bark from trees. Trees are also affected by climate disruption, which leads to intense storms, like those in 1999 and 2009, and severe droughts, like those in 2018. They are also more vulnerable to parasites (e.g. bark beetles). This damage is not compensated by the French government, unlike in the agricultural sector. In addition to these problems, forests are also difficult to manage due to their fragmentation: private forests, which account for 74% of French forests, are divided between 3.5 million owners. Only a third of them have made sustainable management commitments. The price of wood fell by 40% between 1980 and 2015, even as labour costs rose to 75% of forest production costs, belying the old adage “wood pays for forest work”, adds the report from the Court of Auditors. In 2019, “the average selling price of wood also fell by 10% to 60 euros/m3, compared to 66 euros/m3 in 2018, according to the 2020 indicator released by the joint trade association France Bois Forêt. (…) Softwood prices as a whole fell by 5%, a decrease that was noticeably sharper for the Norway spruce, the average price of which fell by 22% to 36 euros/m3”, noted Le Figaro on 18 May 2020.

Lastly, although forests are expanding and wood is being promoted as a biosourced product, logging has prompted “concerns and disapproval” and “eco-anxiety”, to borrow the words of Anne-Laure Cattelot, an MP from the Nord department, in her report Forests and the Wood Industry at a Crossroads: The Tree of Possibilities (July 2020)

THE WOOD INDUSTRY: A GOVERNMENT-BACKED RESPONSE TO CLIMATE DISRUPTION

As noted by Fabrice Denis, VP Strategy, Wood Construction at Bouygues Bâtiment France Europe, “while forests are suffering the consequences of climate change, they also offer a response to it. (…) Lumber can help reduce emissions by 10%; and growing demand downstream will pull the supply side along with it.”

The upcoming environmental regulation (RE 2020), the 200-million-euro relief package announced by Julien Denormandie on 22 December 2020 (which was developed to protect forest resources and plant 50 million trees), and the 70-million-euro Wood Fund created by BPI France, should allow the industry re-organise itself more smoothly.

On 14 December 2020, its Strategy Committee announced a new “2030 Timber Plan”, “to accelerate the diversification of materials and the reduction of carbon emissions”, which it will present in early 2021.

“The wood industry is in the process of opening up to all stakeholders in the construction industry, to share its expertise and discuss constructive practices in the ecological transition. Far from being dogmatic, it is available to all stakeholders who wish to commit to building carbon neutrality. The challenge for RE2020 will also be to ensure that this family of ‘builders’ becomes acculturated to including materials that can store or be used as a substitute for carbon. The wood industry will support and facilitate this change”, it announced in its press release.

(Français) Bouygues Bâtiment France Europe affiche son ambition bois

(Français) Interview croisée de FABRICE DENIS, directeur de la stratégie construction bois de Bouygues Bâtiment France Europe et de MARC FRANCO, directeur de l’agence Coldefy Paris, en charge du projet Wonder Building de Novaxia, construit par Bouygues Bâtiment Île-de-France – Construction privée.

Comment Bouygues Bâtiment France Europe, “le bétonneur”, compte-t-il devenir leader de la construction bois dans dix ans ? D’autant que “construire en bois, ce n’est pas remplacer du béton par du bois”, souligne Fabrice Denis, directeur de la stratégie construction bois de Bouygues Bâtiment France Europe. Explications.

BOUYGUES BÂTIMENT FRANCE EUROPE A EXPRIMÉ L’AMBITION DE DEVENIR LA RÉFÉRENCE EN MATIÈRE DE CONSTRUCTION BOIS. FABRICE DENIS, COMMENT LA RÉALISER ?

F.D. – Grâce à une démarche de transformation, baptisée “WeWood”, avec trois objectifs. Le premier, que 30% des quelques 600 projets annuels de Bouygues Bâtiment France Europe comprennent, d’ici 2030, au moins 100 m3 de bois et/ou 500m2 d’ossature bois, pour limiter notre empreinte carbone, puisque le bois, un matériau renouvelable, a la vertu de séquestrer et de stocker le CO2.

Notre deuxième objectif : permettre une expérience fondamentalement différente à l’ensemble des parties prenantes du chantier car la construction bois est plus rapide, génère moins de nuisance et facilite le travail des compagnons. Cinq à six fois moins de camions viennent livrer les matériaux. Et comme la construction bois est plus ergonomique, elle offre la possibilité d’accueillir plus de femmes sur nos chantiers.

Enfin, le bois est un excellent vecteur d’accélération pour reconsidérer notre métier et construire autrement. Construire en bois, ce n’est pas remplacer du béton par du bois.

Le béton se coule sur le chantier et s’adapte à toutes les dimensions, il suffit d’avoir un coffrage différent. Il permet des arrangements de dernière minute. Le bois oblige à davantage de co-conception, et « à penser » le projet très en amont. Murs, poteaux, poutres ne sont pas fabriqués sur le chantier mais en usine, avant d’être apportés sur le site ; aussi la maîtrise d’ouvrage doit-elle concevoir le projet en fonction des capacités des industriels, en considérant tous les corps d’état architecturaux : ce qui caractérise la construction bois, c’est aussi le complexe global bois et second œuvre (isolation, placo) qui doit être conçu pour répondre aux contraintes acoustiques, thermiques, incendie.

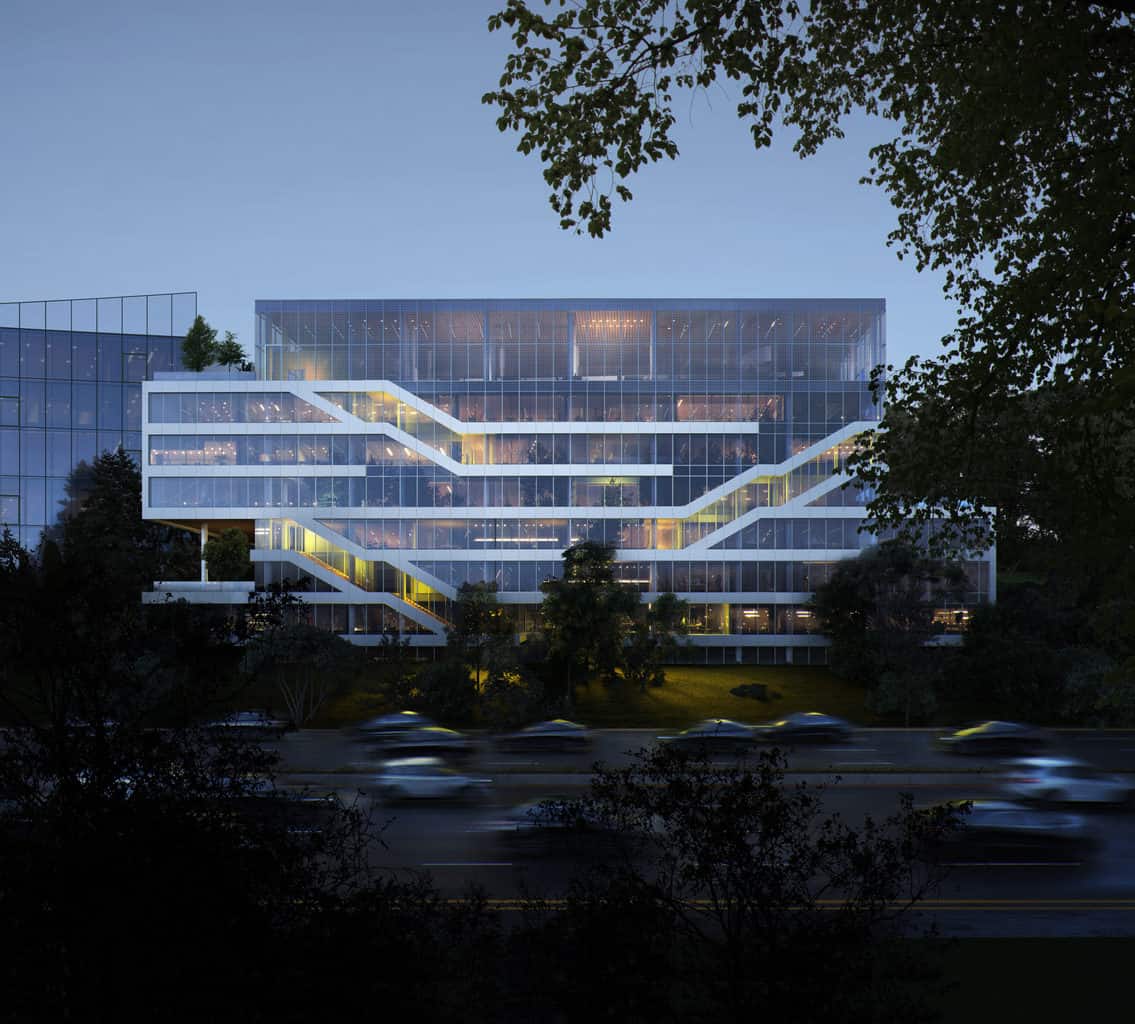

(Français) MARC FRANCO, VOUS ÊTES ARCHITECTE EN CHARGE DU WONDER BUILDING DE NOVAXIA À BAGNOLET, DONT LES TRAVAUX REVIENNENT À BOUYGUES BÂTIMENT IDF. EN QUOI CE PROJET, QUI SERA LIVRÉ EN OCTOBRE 2022, EST-IL EMBLÉMATIQUE DE LA CONSTRUCTION BOIS ?

M. F. – Dans ce bâtiment de 27 000 m2, le bois est quasiment partout – poteaux, poutres, planchers, escaliers… – excepté en façade car le bois grisaille avec le temps et ce n’est pas du goût de tous. En revanche il sera apparent à l’intérieur, protégé par une lasure blanche laissant les veines du bois visibles.

Le bois contribuera à faire de ce bâtiment un lieu vivant. Le bois vieillira doucement, se fendillera par endroit, sans cesser d’apporter aux occupants bien-être et chaleur.

Les arbres des terrasses-belvédères ouvertes sur Paris et Bagnolet, ou ceux du patio intérieur évolueront eux aussi d’une saison à l’autre, d’une année à l’autre.

Les occupants eux-mêmes feront du Wonder Building un lieu de vie, en empruntant les escaliers déportés sur les façades transparentes, donnant sur rue, devenus espaces d’usage… Et en rendant l’intérieur du bâtiment visible à l’extérieur, en faisant entrer l’extérieur à l’intérieur du bâtiment, grâce aux commerces implantés en pied d’immeuble, nous avons doté le bâtiment d’une capacité d’échange entre les salariés et les riverains.

FABRICE DENIS, BOUYGUES BÂTIMENT France EUROPE N’A PAS RÉSERVÉ LA CONSTRUCTION BOIS À UNE ENTREPRISE DÉDIÉE, POURQUOI ?

F. D. – Nous avons écarté cette idée parce que c’est un sujet de transformation culturelle. C’est comme passer de l’essence à l’électrique pour un constructeur automobile, ou, pour Total, du pétrole au solaire. Pour opérer cette transformation, toutes nos entreprises, toutes nos filiales s’initient à la construction bois et à ses enjeux.

A cette fin, nous avons créé une “WeWood Academy”, qui propose à tout le personnel de l’entreprise une offre de formations structurée. En complément, la “WeWood Community”, favorise le partage d’expériences entre collaborateurs et la capitalisation de connaissances, notamment grâce à des “amboissadeurs”, souvent des jeunes ; un novice qui veut mener à Brest un projet de construction en bois pourra s’appuyer sur l’expérience d’un collaborateur à Lyon, par exemple. Enfin, nous allons construire un “club” hyperpartenarial, incluant PME, startups, architectes, pour développer des écosystèmes.

MARC FRANCO, COLDEFY TRAVAILLE DEPUIS LONGTEMPS AVEC BOUYGUES CONSTRUCTION. QUEL AVANTAGE EN TIREZ-VOUS, DE VOTRE CÔTÉ ?

Notre métier d’architecte est comparable à celui de chef d’orchestre ; nous avons une vision globale de la partition à jouer : l’interpréter avec des spécialistes de haut niveau, c’est très agréable !

Nous travaillons ensemble depuis vingt ans et j’apprécie leur savoir-faire. Ce sont de grands professionnels des bâtiments. Ils ont une force de frappe assez incroyable, avec des ingénieurs spécialisés.

La formation, c’est ce qui manque dans nos métiers. Leur transmission du savoir s’opère sur le terrain, entre spécialistes et novices, entre séniors et juniors. C’est un plaisir de voir ça sur les chantiers.

F. D. – Notre première priorité, c’est apprendre à construire en bois, former, avoir des ressources en ingénierie. Nous nous sommes dotés d’un pôle d’excellence de trente ingénieurs experts, tous passionnés, quasiment des activistes ! C’est un bonheur de piloter ces jeunes, car ils veulent faire évoluer les mentalités.

QUELLES SONT VOS AUTRES PRIORITÉS ?

F. D. – Notre deuxième priorité, c’est nous assurer que le bois est issu de forêts gérées durablement, et que tous nos bois soient certifiés PEFC et FSC. WWF accompagne Bouygues Construction vers un approvisionnement responsable en bois.

La troisième, favoriser les circuits courts et les emplois locaux, utiliser quand c’est possible du bois de la région, ou du bois français, même si cela nous revient plus cher. Nous sommes d’ailleurs en train de construire des contrats-cadre instaurant un certain pourcentage de bois français dans nos constructions. Chaque appel d’offres est une opportunité de construire des écosystèmes, car c’est notre intérêt collectif à long terme.

Le choc de la demande pour le bois stimulera à la fois une meilleure exploitation de nos forêts et l’industrie française du bois. Il y a 400 000 emplois liés à l’industrie du bois en France, 1 200 000 en Allemagne !

La demande accélèrera aussi la recherche. Nous poussons, par exemple, une dizaine de programmes de R&D dont un avec un lamelliste de Normandie, pour faire du lamellé-collé en hêtre, propre à la réalisation de poteaux, poutres, plancher ou voiles.

Y A-T-IL VRAIMENT UNE DEMANDE POUR LE BOIS ?

F. D. – La demande est exponentielle. En 2020 elle a été trois fois plus forte qu’en 2019. Les vertus hygroscopiques du bois sur la santé ont été prouvées : dans un hôpital en bois, les gens se soignent plus vite, leurs battements de cœur diminuent. Le bois crée un environnement apaisant. Et puis il permet de dessiner de magnifiques projets, pas seulement des immeubles de grande hauteur. Les investisseurs et utilisateurs sont également sensibles au bilan carbone de la construction. Un bâtiment en bois évite 60% des émissions de CO2 d’un bâtiment en béton sur la partie structure, et 20% tous corps d’état. Certes, à l’achat, un bâtiment en bois est plus cher qu’un bâtiment comparable en béton, mais le coût global dans la durée est inférieur : il permet des économies de chauffage, une location plus facile et plus élevée, il génère donc des revenus supplémentaires.

M. F. – Oui, il y a un fort intérêt pour le bois, avec la prise de conscience de l’état de notre planète. Mais il faut être modéré sur l’utilisation des matériaux, que ce soit le bois, le béton ou l’acier et n’en surexploiter aucun.

LA RÉVERSIBILITÉ DES BÂTIMENTS EST UN ENJEU DE CONSTRUCTION DURABLE. UNE CONSTRUCTION EN BOIS S’Y PRÊTE-T-ELLE PLUS QU’UNE CONSTRUCTION CLASSIQUE, EN BÉTON ?

F. D. – Le bâtiment de demain va être plus flexible, plus hybride. Le bois permet de faire évoluer le bâtiment dans le temps pour qu’il s’adapte aux évolutions successives des modes de vie. Les procédés constructifs, comme le vissage, permettent de reconfigurer plus facilement l’espace intérieur que dans un immeuble en béton dont les connexions sont faites en béton armé. Cela aussi contribue au confort mental des utilisateurs, qui expérimentent, dans un contexte de densification urbaine parfois stressant, un habitat naturel et apaisant.