Under what circumstances can digital technology improve resilience at local level?

8 minutes of reading

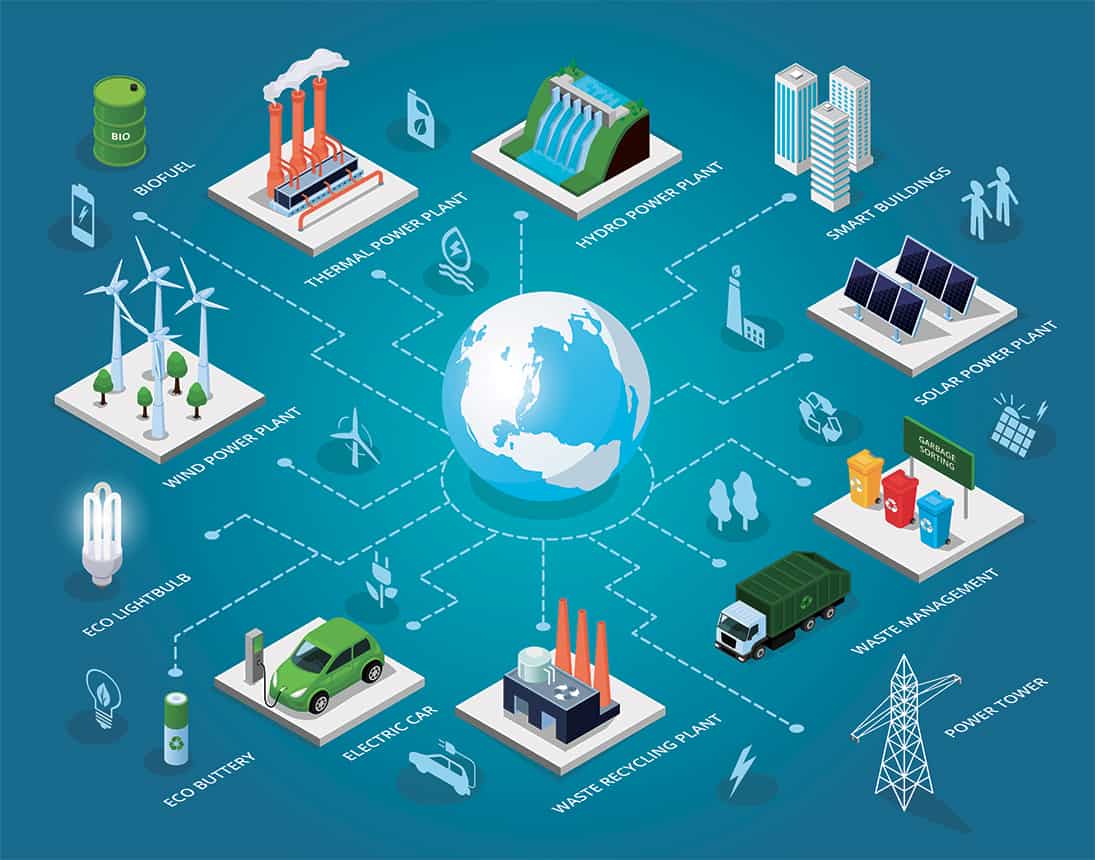

When applied to local communities, the term “resilience” refers to the ability to function independently of disturbances, whether they are sudden and sudden shocks (e.g. flood, riot, terrorist attack) or chronic stresses creating continuous pressure (e.g. air pollution, ageing infrastructure, antisocial behaviour). While digital technology undoubtedly has a role to play in improving resilience at local level, it also carries vulnerabilities. In what situations can there be a positive relationship between the benefits linked to the use of digital technology, and the environmental impacts and vulnerabilities it causes?

Benefits: the example of the digital twin

Data governance is a key tool for anticipating phenomena, understanding and diagnosing local vulnerabilities, modelling future scenarios according to changing climate effects, issuing alerts and managing emergencies. Digital tools can also facilitate systemic approaches and serve as a vehicle for more general stakeholder involvement, and citizens in particular. This is true, for example, of the digital twin for the local community, which represents a virtual replica of a local community in its current operational form. Far from being a mere 3D replica of a geographical area, it aggregates multiple data (regulatory, geospatial, environmental, uses, and also real-time data from sensors) to constitute a representation of the city and create information that will inform action. Architecture, town planning, usage practices and their consequences (property prices, pollution, etc.), networks and their flows, subsoil resources and geological layers are likely to appear in this type of tool. The tool then offers almost unlimited potential in terms of applications; for example, with the ability to simulate or manage a crisis, by exploring disruption scenarios, for example. It is also a powerful tool for transforming organisations because of its systemic approach and its ability to bring stakeholders together around a common framework. As a unified source of data for the local community, it can promote collaboration between services and the de-siloing of business units, and contribute to the implementation of systemic policies that are more effective. This is, for example, one of the stated objectives of the Rennes municipal authority in its deployment of its 3DEXPERIENCity Virtual Rennes tool. However, as the Banque des Territoires points out in its guide: Mirror, mirror…: the digital twin of the local community, the implementation of a digital twin requires real maturity from the local authority in terms of running digital transformation projects and carrying out an analysis of risks and opportunities with regard to ethical, legal and economic issues, technological choices, governance and cybersecurity related to this type of project.Vulnerabilities

Despite these advantages, digital technology is also a source of vulnerabilities in the face of natural hazards, or hazards associated with human activity. A natural hazard can be accompanied by cascading effects leading to the failure of certain digital solutions in a given local community. In 2012, following Hurricane Sandy’s assault on the coast of New Jersey and southern New York State in heavy rains and winds, New York City’s technical networks were particularly badly affected: power outages and disruption of wired, mobile and internet networks for several days. Similarly, acts of cybercrime can paralyse municipal services over a shorter or longer period. In France and abroad, 2020 was marked by a strong increase in cyberattacks affecting local authorities of all levels and of all sizes: Grand Est Region, Departmental Council of Eure-et-Loire, Aix-Marseille Metropolis Provence, the urban community of La Rochelle, the town of Bondy (53,439 inhabitants) and the town of Saint-Paul-en-Jarez (4,831 inhabitants). Such cyberattacks underpinned the need for the creation in 2020 of a national institute for cybersecurity and resilience in local communities. Digital technology is also having a strong impact on ecosystems: it is responsible for nearly 4% of global carbon emissions, i.e. double that of civil air transport, and produced 53.6 million tonnes of non-recyclable or barely recyclable electrical and electronic equipment in 2019 – an increase of 21% over 2014, according to the World Electronic Waste Observatory.Sobriety and right-tech: using appropriate and sufficient technologies

Consequently, there is a need to quantify the relationship between (a) the benefits linked to the use of digital technology and (b) the environmental impacts and the vulnerabilities induced (in the face of natural hazards and the risks of electrical power cuts and cybercrime). Tools have been developed for this purpose, such as the STERM mathematical model (Smart Technologies Energy Relevance Model) designed by The Shift Project to analyse the net energy relevance of connected projects. The tool’s code is freely accessible in order to encourage its use by private and public actors, and to enable them to develop operational tools tailored to their needs. In an interviewed with Usbek & Rica, Maxime Efoui-Hess – one of the authors of the “Deploying digital sobriety” report – deciphers the issues linked to this type of tool: “In some cases, when we add a layer that is “connected” to a lamp, it enables us to directly save energy compared to what would have been consumed without this layer. But we also need to take into account the energy that has been consumed to produce this system, and the consumption of the connected system itself. These issues are complex, but the methodological tools for carrying out these evaluations are there. We must now find a way of putting them in place.” More generally, the emerging concept of “right-tech” offers a frugal path of innovation: using fair and sufficient technologies to meet an identified need, while ensuring compliance with strong environmental constraints. Breaking with the principles of the rapid pursuit of technology and complexity, the right-tech approach is inspired by “low-tech” principles, yet without ruling out the use of advanced technologies where relevant, and with regard to environmental forecasts.Experience feedback: the ON Dijon connected oversight centre during the Covid-19 health crisis

There is no substitute for feedback from a disturbance when assessing the resilience of a local community: during the Covid-19 health crisis, the first spring 2020 lockdown demonstrated the efficiency of the ON Dijon connected oversight centre (with Bouygues Energies & Services a member of the consortium in charge of construction and management). Inaugurated in 2019, the digital platform for the city of Dijon and the 23 municipalities of the metropolitan area provides centralised management for all urban equipment (traffic lights, tram traffic, public lighting, video protection, water system management, etc.). With this large-scale Open Data project, the various community services had acquired the habit of working together, and controlling the equipment remotely and in real time made it easier to manage the health emergency: traffic lights to give priority to emergency vehicles; remote locking and monitoring of all empty public buildings, thus avoiding having agents on site; priority given to buses at intersections to ensure that the caregivers involved lose as little time as possible in transit. The Allo Mairie service was transformed into a toll-free number accessible 24 hours a day during lockdown, enabling citizens to ask all their questions related to the crisis, with the exception of medical questions. The telephone portal thus changed from an information service on municipal services (eg swimming pool opening hours) to a number oroviding information on local and national decisions. Between March 15 and April 13, 2020, nearly 4,650 calls were processed (local travel certificates, opening of shops and schools, fake news, measures to end the lockdown, etc.). In particular, the community was able to answer questions about waste management and encourage people to avoid visiting the recycling centre in large numbers upon reopening, to avoid congestion and large gatherings. As a result of these calls, 95 people who were isolated and unknown to the communal social action centre were able to make themselves known. By promoting the flow of exchanges, an ability to respond quickly and the improvement of coordination between services, the tool has helped to strengthen the local community’s resilience in the face of this crisis. However, it is also calibrated to deal with other types of disturbances. In anticipation of a risk of flooding, for example, it centralises data relating to the measurement of the water level and can launch and circulate alerts quickly if an event is imminent. Ultimately, a citizen participation application will be built in, promoting citizen mobilisation and taking advantage of the skills at their disposal.Most read

More reading

Read also

What lies ahead? 7 megatrends and their influence on construction, real estate and urban development

Article

20 minutes of reading