‘Paris at 50°C’: a fact-finding mission to prepare Paris for future heatwaves

2 minutes of reading

in partnership with

To better prepare for the extreme heat forecast in the years ahead, the City of Paris has commissioned a fact-finding mission to look into the issue. After more than 6 months’ work, the city has drawn up 85 recommendations which are contained in a report aimed at adapting the capital.

In a Lancet study on global health published in March this year, Paris was recently ranked as Europe’s deadliest city in the event of a heatwave. Researchers have compared a range of data from more than 800 cities over the last 20 years (weather data, demographic statistics, building infrastructure, etc.) and have come up with an estimate of the risk of excess mortality linked to extreme temperatures, as well as the impact on people’s health. Paris tops this grim list. The main culprits are the materials used in the city’s construction and the urban planning, which are highly unsuited to hot weather and which create numerous urban heat islands.

However, the City of Paris did not wait for this ranking to be published before becoming aware of the situation and starting to (re)act. This has been seen, for example, in the city’s Climate Plan, or its bioclimatic Local Urban Plan, adopted in June after a 2-year consultation period, which outlines the guidelines for adapting Paris to climate change by making the city more frugal and more respectful of the environment.

An information and evaluation mission (MIE) was also launched at the July 2022 Council of Paris, the subject of which was ‘Paris at 50 C: policies for adapting the city to extreme heatwaves.’ Over the course of 6 months, the taskforce, led by councillors from all political backgrounds, interviewed a wide range of key players, including the city’s departments and services, architects, town planners, researchers, associations and trade unions, etc.

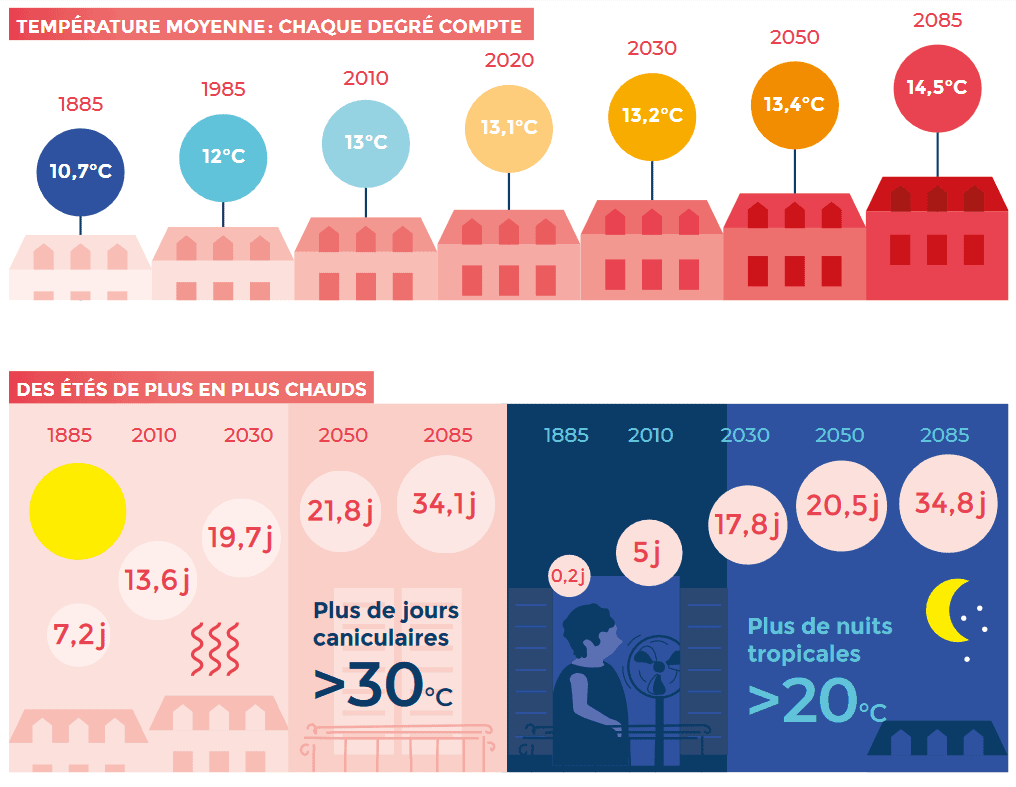

The aim of this MIE was to anticipate as far as possible a situation that will occur between now and 2050, i.e. the intensification and reoccurrence of extreme heatwaves of up to 50°C. The result is a comprehensive report that takes stock of the city’s past and current policies, and puts forward 85 recommendations for continuing to transform the capital.

This major undertaking is interesting in many ways. Although it focuses on the specific characteristics of Paris, this report is a collaborative, transpartisan effort that has been carried out over a long period of time. It integrates multiple areas of expertise, and all at the scale of a capital city. While not all the recommendations apply to all towns and cities, it would be in their interest to learn from this report. Most of our cities are old and were built using a high proportion of construction materials and infrastructures that are not suitable for current and future changes. They are already affected by the challenges of adapting to heatwaves.

As a starting point, what is clear from this report is the need for in-depth action as regards the ‘structure’ of our cities. Here is a summary of the report’s key recommendations.

An information and evaluation mission (MIE) was also launched at the July 2022 Council of Paris, the subject of which was ‘Paris at 50 C: policies for adapting the city to extreme heatwaves.’ Over the course of 6 months, the taskforce, led by councillors from all political backgrounds, interviewed a wide range of key players, including the city’s departments and services, architects, town planners, researchers, associations and trade unions, etc.

The aim of this MIE was to anticipate as far as possible a situation that will occur between now and 2050, i.e. the intensification and reoccurrence of extreme heatwaves of up to 50°C. The result is a comprehensive report that takes stock of the city’s past and current policies, and puts forward 85 recommendations for continuing to transform the capital.

This major undertaking is interesting in many ways. Although it focuses on the specific characteristics of Paris, this report is a collaborative, transpartisan effort that has been carried out over a long period of time. It integrates multiple areas of expertise, and all at the scale of a capital city. While not all the recommendations apply to all towns and cities, it would be in their interest to learn from this report. Most of our cities are old and were built using a high proportion of construction materials and infrastructures that are not suitable for current and future changes. They are already affected by the challenges of adapting to heatwaves.

As a starting point, what is clear from this report is the need for in-depth action as regards the ‘structure’ of our cities. Here is a summary of the report’s key recommendations.

An information and evaluation mission (MIE) was also launched at the July 2022 Council of Paris, the subject of which was ‘Paris at 50 C: policies for adapting the city to extreme heatwaves.’ Over the course of 6 months, the taskforce, led by councillors from all political backgrounds, interviewed a wide range of key players, including the city’s departments and services, architects, town planners, researchers, associations and trade unions, etc.

The aim of this MIE was to anticipate as far as possible a situation that will occur between now and 2050, i.e. the intensification and reoccurrence of extreme heatwaves of up to 50°C. The result is a comprehensive report that takes stock of the city’s past and current policies, and puts forward 85 recommendations for continuing to transform the capital.

This major undertaking is interesting in many ways. Although it focuses on the specific characteristics of Paris, this report is a collaborative, transpartisan effort that has been carried out over a long period of time. It integrates multiple areas of expertise, and all at the scale of a capital city. While not all the recommendations apply to all towns and cities, it would be in their interest to learn from this report. Most of our cities are old and were built using a high proportion of construction materials and infrastructures that are not suitable for current and future changes. They are already affected by the challenges of adapting to heatwaves.

As a starting point, what is clear from this report is the need for in-depth action as regards the ‘structure’ of our cities. Here is a summary of the report’s key recommendations.

An information and evaluation mission (MIE) was also launched at the July 2022 Council of Paris, the subject of which was ‘Paris at 50 C: policies for adapting the city to extreme heatwaves.’ Over the course of 6 months, the taskforce, led by councillors from all political backgrounds, interviewed a wide range of key players, including the city’s departments and services, architects, town planners, researchers, associations and trade unions, etc.

The aim of this MIE was to anticipate as far as possible a situation that will occur between now and 2050, i.e. the intensification and reoccurrence of extreme heatwaves of up to 50°C. The result is a comprehensive report that takes stock of the city’s past and current policies, and puts forward 85 recommendations for continuing to transform the capital.

This major undertaking is interesting in many ways. Although it focuses on the specific characteristics of Paris, this report is a collaborative, transpartisan effort that has been carried out over a long period of time. It integrates multiple areas of expertise, and all at the scale of a capital city. While not all the recommendations apply to all towns and cities, it would be in their interest to learn from this report. Most of our cities are old and were built using a high proportion of construction materials and infrastructures that are not suitable for current and future changes. They are already affected by the challenges of adapting to heatwaves.

As a starting point, what is clear from this report is the need for in-depth action as regards the ‘structure’ of our cities. Here is a summary of the report’s key recommendations.

Renaturalise to cool

It is impossible not to mention this, as it is the main recommendation of any study on the subject. The removal of asphalt needs to be sped up and needs to be as extensive as possible. The Climate Plan already addresses this point (the objective was to reduce the amount of asphalt in public spaces by 100 hectares and to achieve 40% permeability by 2040), but here it becomes a must for successful adaptation. Whether it is city streets, squares, crossroads, building courtyards, school playgrounds or car parks, it is essential to plant vegetation in the open ground, to remove the impermeability, to allow water to penetrate the soil and to facilitate the evapotranspiration of plants as a result, which is vital for proper cooling. It is also recommended that porous coatings be used where the removal of asphalt is not possible. This return to natural soil goes hand in hand with the greening and overall renaturalising of the city. The amount of green space and shaded areas should be increased wherever possible. The report recommends not shying away from using participatory approaches to speed up the greening process. This is in addition to increasing the resources and size of the city council’s green space teams. The ultimate goal is to have 300 hectares of green space open to the public by 2040. In areas of shade created by vegetation, pergolas and shading structures could be added where this is easier, particularly because of the many underground tunnels that make up the city’s subsurface (metro lines, sewers, etc.).

Adapting buildings and infrastructure

As far as buildings are concerned, in addition to allocating resources to thermal renovation (an essential step if adaptation is to succeed), the recommendation is to move forward as quickly as possible on the revision of renovation standards for new buildings to ensure that what is done today will be suitable for the future. This is a dialogue to be conducted between local public players (cities, regions) and the State. Greening façades most exposed to the heat is a recommendation that is in line with the principle of renaturalising and exterior cooling, but which will also help to reduce the temperature inside buildings. The roofs of Paris, which are an integral part of the local heritage, are a central issue in the adaptation. The development of collective roof terraces should be encouraged wherever possible, with water collectors and plants. If this is not possible, the roofs could be painted with a white or light-coloured coating to enhance the albedo (reflective) effect. Water also has significant cooling potential. The report notes, however, that it is a scarce and crucial resource with significant issues at stake. It is important to distinguish between drinking water and non-drinking water for each use. Non-drinking water should be used to water plants. Increasing the number of drinking water and refreshment points is essential. There needs to be better access to water with the presence of dynamic fountains or water mirrors, and progress needs to be made on access to swimming for Parisians (Canal de la Villette, banks of the Seine). The idea would be to build at least one, small ‘oasis’ area in each neighbourhood. The report highlights the need to preserve existing air corridors and the city’s natural breathability. There is also a need to plan for the creation of new air circulation corridors. It should be noted that the report recommends that, in order to promote air circulation in homes, a minimum ceiling height of 2.70 m should be encouraged in all new buildings and the creation of dual aspect accommodation in all new buildings should also be encouraged.Tools and funding are essential

Lastly, the report stresses the tools needed by the authorities to manage the adaptation of cities and to ensure that information and data are properly fed back to optimise the actions undertaken. A first step has already been taken with the recent creation of the Department of Ecological Transition and Climate (DTEC) within the organisational structure of the City of Paris. The fact that climate change is a major issue for the city can be highlighted by the existence of this fully-fledged department, as well as the fact that the initiatives are being managed by an independent organisation. This also ensures greater consistency. In conclusion, the report makes a number of recommendations that are essential to the success of all these initiatives. Firstly, to make better use of public procurement as a means of accelerating the city’s transformation. State funding for regional ecological transition projects should be increased, and a European fund should be set up to lend directly to local authorities. Lastly, communication and arbitration should be improved by creating a body to coordinate funding between the State, the Region, the Metropolis and the City.More reading

Read also

What lies ahead? 7 megatrends and their influence on construction, real estate and urban development

Article

20 minutes of reading