Setting up a regional resilience programme

6 minutes of reading

In late 2020, Bouygues Construction, Banque des Territoires and Chronos (an urban innovation consulting firm), with the support of France Ville Durable, held a retreat to discuss the topic of setting up a regional resilience programme. Using an array of assessment tools and regional initiatives, the attendees identified the key factors needed to formalise a regional resilience programme. France Ville Durable, Cerema, AEME, the French High Committee for National Resilience, the Paris Région Institute and the Grenoble Urban Planning Agency spoke of the dedication shown by those involved in this subject, and animated discussions on how to formalise the concept of regional resilience.

Resilience must be the centre of every public policy

Sébastien Maire, Managing Director of France Ville Durable and the former Chief Resilience Officer for the City of Paris, set the stage during the introduction: resilience is not a public policy like any other, but must in fact be central to the development of every policy. Only then will a region be able to continue its activities despite the disruptions it may face, whether they be acute shocks (floods, heat waves, pandemics, industrial accidents, fires, etc.) or chronic stresses (air pollution, a lack of social cohesion, poverty and inequality, ageing infrastructure, a lack of affordable housing, etc.). The ingredients needed to do so are already known, said Sébastien: organising collaborative workshops to rally and band together regional actors, incorporating resilience into local governance with resilience offices, and performing shared assessments—an essential step before designing a regional resilience strategy and its operational implementation. However, these are long-term steps that require a strong boost from public decision-makers.Regions will have a broad toolbox to rely on, but must design their own approach to regional resilience

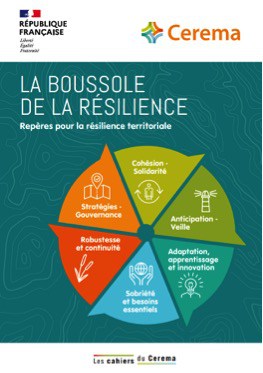

The same is true for regional resilience tools. Real expertise has developed over the last few years, providing local governments with a wide range of tools designed for international organisations, consultants, associations and national institutions. The retreat was an opportunity to highlight two of these tools:- The regional resilience compass, developed by the Centre of Expertise for Regional Actors (Cerema), whose launch coincided with the date of the workshop. According to Aurore Cambien, Regional Resilience Project Manager at Cerema, the purpose of this document is to provide guidance to regions in order to improve their ability to prepare, react and adapt to the various disruptions that may arise, whether acute shocks or long-term changes. This guide, which is broken down into 6 levers and 18 principles, can be used to analyse any project or public policy, in order to offer adequate responses to present or future hazards.

- The Orange Pavillion label, bestowed by the French High Committee for National Resilience to municipalities that meet certain criteria for safeguarding and protecting their populations against major risks. The label is an extension of national regulations, and incorporates the recommendations of the General Directorate for Civil Defence and Crisis Management. Some sixty French cities have received the label, according to Christian Sommade, Managing Director of the French High Committee for National Resilience.

A holistic or issue-based approach?

Although resilience must necessarily be approached holistically and systematically, it can also originate with a specific risk. That was one of the messages given by Ludovic Faytre, “Risks/Planning” Research Manager at the Paris Région Institute, who presented his work on reducing vulnerability to flooding in the Paris Region. In the Paris Region, the effects of a major flood would go well beyond the flooded areas alone, and would impact the entire region due to the convergence of systemic issues and vulnerabilities: life-threatening events, structural damage, disruptions or interruptions of public services (health care, education), networks (power, transportation, drinking water, sanitation) and economic activities, and threats to people’s basic needs (shelter, provisions, etc.). According to Ludovic, understanding and accepting one’s own vulnerability is certainly the first step toward resilience, and measures to reduce it are necessarily varied: protections (levees), network and infrastructure modifications, special planning for flood-prone areas, a culture of risk (awareness), business continuity plans for companies and public services, etc.A general or targeted approach?

“Resilience isn’t just about crisis management, it goes much further than that”, reiterated Sébastien Maire. Is resilience necessarily related to immediate hazards, the attendees asked themselves, or is it also more general, focusing on slow, large-scale phenomena (e.g. climate change)? Can a region be resilient to all disruptions? Is resilience not a process instead, one that relies on certain essential pillars:- Robustness: limiting the spread of breakdowns by anticipating domino effects

- Inclusivity: the involvement of all stakeholders (populations, businesses, etc.) in the general process of governance, as “the sum of all individual resiliencies does not equal collective resilience”

- Integration: a cross-cutting approach favoured for its ability to create numerous benefits (e.g. Benthemplein water square, a flood-prone public space that can be used as an amphitheatre or sports venue when the weather is dry)

More reading

Read also

What lies ahead? 7 megatrends and their influence on construction, real estate and urban development

Article

20 minutes of reading