[Panorama Sustainable Cities] #2 The Concept of “Sponge Cities” in China

4 minutes of reading

in partnership with

The concept of “sponge cities”, launched by the Chinese government almost ten years ago, presents a way to mitigate the effects of floods in large cities and to recreate the natural water cycle in urban areas. The idea is to optimise overall management, from recovery to use. These adaptations for better resilience are currently taking place in 30 cities.

Cities around the world, sometimes swelling to the size of metropolises or megacities with several million inhabitants, have chosen concrete and stone to feed their growth and sprawl. The problem is that these materials are highly impermeable.

What these cities did not anticipate was that climate change would give rise to increased intensity of rainfall and that climate hazards would become extreme. The impermeability of cities, resulting from mass-scale artificialisation of soils coupled with outdated and largely insufficient drainage systems, has led us to witness increasingly frequent phenomena of destructive flooding during episodes of heavy precipitation in urban areas.

The urban model also puts major constraints on the natural water cycle. Rainwater is discharged further downstream in one way or another, usually ending up in a river or the ocean. Therefore, it no longer seeps through the soil to reach the local groundwater. This has brought about a grave paradox for these metropolises, as they have grown vastly more vulnerable to floods while also suffering intensely from periods of drought and drinking water shortages. To compound matters, the global phenomenon of rising sea levels, that particularly affects coastal cities, now constitutes a third threat to the urban model as we know it.

China is particularly vulnerable to these three phenomena. The magazine Pour la Science estimated that, from 2011 to 2014, 62% of the country’s cities experienced flooding, which led to economic losses of 100 billion dollars. Faced with this global issue of water management, the country decided to take action and invest heavily in a new model in 2014: “Sponge cities”.

Improving urban resilience

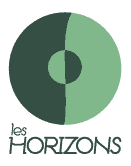

Sixteen cities were selected to begin with, for the creation and instalment of large permeable areas. Designed to replace traditional drainage networks, these areas were to provide cities with the benefits of a natural environment, helping to protect them from the hazards of the three phenomena. This model has now been applied in 30 cities, including Beijing, Shenzhen, and Shanghai. The goal is ambitious: to ensure that by 2030, 80% of China’s urban areas are able to absorb and reuse 70% of the torrential rainwater that affects them. Like Australia’s model of water sensitive cities, the concept of sponge cities aims to make urban areas resilient and adapted not only to episodes of heavy rainfall, but also to episodes of drought and water scarcity, through a return to nature that allows cities to cool down and secure their own water supply. The idea is therefore to apply the principle of a sponge to a highly urbanised environment, giving it the capacity to absorb, capture, and store rainwater. There must also be a capacity to reuse this rainwater once it has been cleaned and depolluted. To achieve this, major adaptations had to be performed in the cities. This involved putting a stop to the use of impermeable materials and aiding the process of soil infiltration by using porous materials. This, of course, goes hand in hand with a policy of creating green spaces, wetlands, rain gardens, bio-retention systems, green walls and roofs, and underground reservoirs under parks to store rainwater in case of excess and prevent drainage system saturation. Porous materials are thus systematically used for roads and sidewalks. Water retention basins are placed in strategic positions such as under parks or playgrounds. In this way, a whole network for managing rainwater is set up so that the city can store or transport water according to its needs. A “sponge city” therefore accompanies the natural water cycle rather than diverting it.Putting the natural water cycle back at centre stage

In Hebi, a system combining porous asphalt with an underground cell system has been set up to recover rainwater over several square kilometers. This water can be stored and used later. The Lingang district of Shanghai – a city particularly exposed to rising waters due to its coastal position – is a similar case, testing the sponge city model. Here, the streets are built with permeable materials, there are open areas in the centre filled with plants, and reservoirs have been installed under the gardens. An artificial lake has even created for the purpose of water storage. The Sponge Cities programme has also allowed the city of Wuhan to recreate large wetland areas and lakes outside the city, to act as buffer zones during heavy rainfall episodes. In fact, a hundred lakes in the surrounding area had been filled in to make way urban sprawl. However, two obstacles stand in the way of such colossal works: the considerable length of time they take to implement, meaning that significant structural choices must be made individually for each city (the task evidently grows even more complicated when it comes to old neighbourhoods whose design hinders renovation); and their exorbitant cost. A comprehensive cost estimation of the programme in China is complex to establish, but several tens of billions of euros will be required if cities are to achieve the goals. According to Pictet Bank, this sum could reach up to 200 billion euros. And the Chinese government only pays 20% in public subsidies. For municipalities, the rest has to be sought from the private sector. However, the model does seem to be gaining ground as it inspires others to follow: for example, the cities of New York, Montreal, and Toronto. The city of Berlin has already implemented a series of measures to become a sponge city and has apparently earmarked a massive investment (of 10 billion euros) to continue the adaptations. While the first results in China have been rather encouraging so far, the country experienced a hellish summer with the passage of Typhoon Doksuri that brought record floods to Beijing and the neighbouring province of Hebei. The reservoirs played their part, but the weather was exceptionally violent. This shows the extent to which cities need to continue to adapt and invest ever more in such systems.More reading

Read also

What lies ahead? 7 megatrends and their influence on construction, real estate and urban development

Article

20 minutes of reading