What kind of governance is appropriate for a convivial city?

5 minutes of reading

At the request of Bouygues Construction and La République des Hyper Voisins, six students from the École Urbaine at Sciences Po Paris worked for nine months on creating conviviality in urban areas. The proposed exploration strategy is to create the conditions for conviviality by introducing a professionally-structured form of citizen action on a micro-local scale. Explore their recommendations for the forms of governance that are most conducive to the emergence of convivial spaces, based on eleven areas of investigation in France and Switzerland.

Conviviality as a common good and an economic asset

300. This is the number of convivial objects, both tangible and intangible, listed in an “inspiration booklet” for convivial public spaces produced by the Institut Paris Région. A bench, a mobile shop, an art trail, a pedestrian zone, etc.; there are many ways to create public spaces that generate well-being and conviviality. But what exactly is conviviality? According to Ivan Illitch, thinker and author of the essay Conviviality, conviviality can be viewed as the “continuous, autonomous and creative interrelations between people, and between people and their environment.” Conviviality is therefore based as much on a spatial reality that forms a local space as on the links forged between individuals and the collective measures undertaken. The act of stimulating and energising interactions between people living in the same area creates value and wealth. In this respect, conviviality can be viewed as a communal asset, which may even have economic value. This communal asset relates not only to collectively managed resources but also to the ability to live together collectively. The positive externalities of conviviality are numerous. Familiarity and recognition between neighbours reinforces a climate of security, help and benevolence between the inhabitants, and is conducive to the emergence of local solidarity. Conviviality also has a positive financial impact: by increasing the use of public spaces, it supports the establishment of new money-making activities, sometimes accompanied by the creation of jobs, and can reduce damage to public space.New ways of “professionalising” conviviality

Although collective action is the breeding ground for conviviality, this study focuses on the factors that create and support such conviviality. Local communities did not waste time waiting for institutions to generate conviviality. Neighbourhood shops and caretakers have been historical players and essential links in the vitality of a neighbourhood, as have associations and volunteer networks. But today, the urgent need for conviviality calls for the development of other systems. The Covid-19 crisis has shown the extent to which local social capital is crucial to building resilience. During the lockdowns, a number of initiatives were launched in local communities via the grass-roots mobilisation of ordinary citizens, local elected representatives and local economic stakeholders. The response to this extraordinary period was driven partly by the ability of all the actors to mobilise collectively and with social agility around a common objective, and partly by the ability to keep on functioning as a society. Faced with this increased demand, new forms of professional structures are emerging. This involves creating top-down or bottom-up conviviality through citizen or private initiatives that provide fuel for public action. This requires cooperation between all stakeholders: local authorities, associations, citizens and private actors.

In Rotterdam, since 2015, a “square manager” has been working as a manager and coordinator of the installations and events programme for the Schouwburgplein square in the city centre. The manager’s role is to care for the square as a public space throughout the year to promote social encounters and interactions. The team works closely with the surrounding cultural institutions, business and residents’ associations and the town hall. The initiative has been a real success and has transformed the image of the square, which had received many complaints a few years ago. Sporting, cultural and civic events are held there throughout the year, and the team also works alongside the town hall on the design of the square to improve the way in which it works. Since then, the local authorities have approached the stakeholders to develop similar programmes in other squares of the city.

Training “conviviality agents”

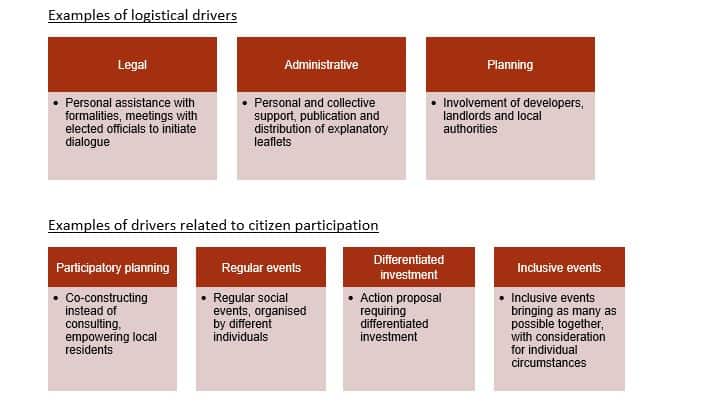

A similar approach is being taken by the Republic of Hyper-Neighbours, a co-sponsor of the study. For several years, the association has been working to develop conviviality in a neighbourhood of the 14th arrondissement of Paris. Through a number of measures, it invites residents to forge links to reawaken a dormant sense of conviviality: giant meals in the street, greening, creation of bio-waste channels, and appropriation of public space through usage control. The mission has been a success, with local residents jokingly reporting that it takes them twice as long to do their shopping now that they know their neighbours in the neighbourhood and talk to them. The next step is to develop this type of scheme in other neighbourhoods and to train community workers, the “neighbourhood friends” who can coordinate the social engineering linked to these actions. To this end, the creation of a “school of relationships” is planned. Throughout the study, the students guided the implementation of the measures to provide a professional basis for this conviviality, identifying the governance structure most conducive to the emergence of a convivial territory, based on a community of local residents. This work categorises the networks of stakeholders supporting the development of this conviviality through citizen initiatives in eleven fields of investigation: the Popular University of Grande-Synthe (59), Mon Voisin des Docks (Saint-Ouen), three neighbourhoods in Switzerland (Erlenmatt in Basel, Eikenott in Gland and Eglantines in Morges), the Ressourcerie Créative in Paris, etc. It identifies the driving factors in the process of creating and developing conviviality, both logistical and linked to citizen participation. Finally, this work includes recommendations for creating a professional “conviviality agent” role, including a preliminary job description for this type of actor, the definition of conditions favourable to his or her work, and a prospective scenario for the successful implementation of such a conviviality agent role in a fictitious neighbourhood.

In conclusion, conviviality is a powerful instrument for designing the public space of a neighbourhood, and can considerably change its face. Its development requires concerted efforts by all stakeholders, which can be facilitated by a resource-driven policy that leads to a “professionalisation” of social cohesion based on new figures such as “conviviality agents” and “neighbourhood friends”.

Finally, this work includes recommendations for creating a professional “conviviality agent” role, including a preliminary job description for this type of actor, the definition of conditions favourable to his or her work, and a prospective scenario for the successful implementation of such a conviviality agent role in a fictitious neighbourhood.

In conclusion, conviviality is a powerful instrument for designing the public space of a neighbourhood, and can considerably change its face. Its development requires concerted efforts by all stakeholders, which can be facilitated by a resource-driven policy that leads to a “professionalisation” of social cohesion based on new figures such as “conviviality agents” and “neighbourhood friends”. Most read

More reading

Read also

What lies ahead? 7 megatrends and their influence on construction, real estate and urban development

Article

20 minutes of reading

Energy

in partnership with

‘Paris at 50°C’: a fact-finding mission to prepare Paris for future heatwaves

Article

2 minutes of reading

What if your sites were supplied via rivers instead of roads?

Article

3 minutes of reading