Paris 2024: building a legacy for the region

5 minutes of reading

in partnership with

While the tradition of building Olympic villages dates to 1924, when the last Paris Games were held, it was not until 2003 that the legacy dimension of the Games appeared in the Olympic Charter. SOLIDEO, the delivery authority for all the permanent works of the coming Paris Olympic Games, has put this idea of a reduced or positive long-term impact at the heart of its plans to prepare for the post-Olympic period, for example by favouring renovation over new construction.

While some developments have already been strongly criticised, can the 2024 Olympics be a new model for Olympic urban planning? How can we work to build a shared and positive legacy of this event for cities?

The Paris Olympic Games: two centuries, two ethoses

In 2024, Parisians will host the Olympic Games for a second time. As in 1924, mainly due to the lack of free space to host the structures within the capital, there was a strong focus on the Parisian suburbs while planning the Games. While a century separates the 1924 Games from those of 2024, changes in the organisation of the Olympic Games have occurred between these two dates that present new challenges, particularly the differences in the political and economic landscape and in the regional approach with two very different planning styles. First, the financial stakes, associated with the professionalisation of sport, are nowhere near as high as they were in the past. Over time, the Olympic Games have also become a significant event, both politically and even ideologically. Similarly, the planning ethos induced by the Games’ organisation was not at all the same as at present. The often-temporary nature of the facilities also shows a lack of consideration and anticipation of the future use of the various facilities and equipment. While some are still in existence following the Paris Games, others such as the Olympic Village have been demolished. This approach is no longer appropriate in a context where saving resources and reducing carbon emissions have become essential. So how can we deal with the significant social and environmental impact of this ground-breaking event? What means should we put in place so that we can design and reinforce an event that will benefit the whole region in the years to come? The organisation of this new edition intends to embrace this challenge, as it wishes to be integrated into a wider development plan, that of Greater Paris. The aim? Anticipating this time, the redevelopment and future uses of the various facilities in order to ensure that the developments are carried out in a more sustainable, environmental and responsible manner.

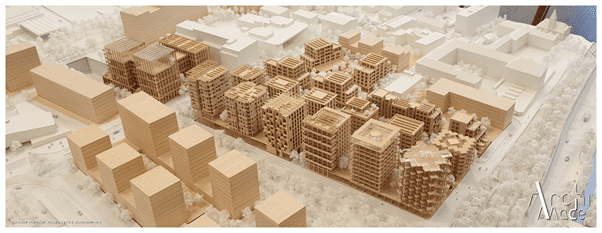

Model of the Paris 2024 Olympic Village. Credit maquettesarchimade.fr

A change of approach for tomorrow

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) decided that all future editions of the Games should be “climate positive”. So, from 2030 onwards, each organising committee will be required to minimise the impact of the Games as much as possible, to compensate for the carbon emissions produced and also to put in place sustainable solutions. However, the organisers of Paris 2024 have decided to act before the 2030 deadline. The way to initiate change for the Games, to provide a new model and to inspire future editions. So, the aim is to become the first edition that positively impacts on the climate, with a commitment to achieving carbon neutrality for the whole project. Consequently, the carbon footprint is expected to be half that of the previous Summer Olympics. Paris 2024 will also offset more than 100% of its residual emissions, becoming the first Olympic and Paralympic Games in the world to have a positive impact on the climate. This approach has already been initiated with the construction of future Aquatic Centre built for a sporting event, which tends to be a model in terms of energy performance. Effectively, this location will become one of the largest urban solar farms in France in terms of energy self-sufficiency. The entire structure and furnishings of the Aquatic Centre were built with renewable or reclaimed materials, such as sustainable wood or recycled plastic. It will also be the first sports facility dedicated to the Olympic Games whose stadium seating will be made entirely from plastic caps. Innovatively, this project responds to a dual environmental and social challenge, as these custom-designed seats will also be manufactured in France by a local company and from plastic waste collected in partnership with local organisations.

Photo credit Florian Muller from Unsplash

What is the legacy for Seine-Saint-Denis?

“The Games were primarily envisaged in terms of a regional legacy for the populations that needed them most”, highlighted Prime Minister, Jean Castex. So, even though the Olympic Village has been designed to accommodate thousands of Olympic and Paralympic athletes during the summer of 2024, once the Games are over, the district will be converted into a complete urban district. In total, this will be more than 11,000 homes, 120,000m2 of offices, 3,200m2 for shops, a 3-hectare developed park, 7 hectares of green spaces and a redeveloped gymnasium will be created. The dense plots of buildings up to 10 storeys high were designed to be quickly renovated after the Games. In the dwellings, the partitions and lifts are dismantlable and will be reused in the construction of other nearby urban projects. All of the developments and construction works carried out to host the Olympic Games will tomorrow be a legacy, fully integrated into the functioning of the cities in which they happened. In France, the recognition of the concept of legacy has resulted in the establishment of what promoters, lawyers and urban planners are now calling Olympic urbanism. Regulated by classic urban planning and environmental rules, it is emerging as a new two-speed urban planning model SOLIDEO, the Olympic Games delivery authority, a public body created in 2017, is responsible for the construction of the sustainable Olympic village.Towards a participatory Olympic urbanism?

Finally, beyond the short duration of this event, global and local issues tend to have a lasting impact on their host cities. The promotion of sport and its associated ideologies is generally accompanied by a growth of available sports in the area where Olympic facilities have been developed. Moreover, if the regional strategies undertaken by the host city are successful, the Olympic Games can represent a valuable springboard for the development of the region, particularly regarding tourism and the economy in the following years. The Olympic Village, the emblem of the Games, also plays an important role in building the memory and international reputation of a new urban model of an eco-friendly city. Against this backdrop, additional resources are available to the developers, with a view to creating real urban communities in a very limited time, but also to guarantee their sustainable integration after the Olympic Games. However, although the construction of the Olympic villages is now bringing renewed attention to the issues of legacy and ecology, for the inhabitants it is still a potentially traumatic process of rapid transformation of their urban environment. This is also essential for the development of urban communities that are integrated into their environment. This is why SOLIDEO and representatives of the Organising Committee of the Games (OCOG), invited the inhabitants and organisations of Seine-Saint-Denis to give their opinion and comment on the future use of the structures built for this sporting event. A first step that many may consider to be inadequate. More than a consultation with residents, it would be exciting to co-construct the facilities that will host the Games for a short time with those who actually live in the area. In this way, local stakeholders, shopkeepers, businesses and organisations could participate in the design of future facilities, thus encouraging better acceptance and ownership of the projects. Thus, each facility could reflect the environment in which it is located, whether from a social or cultural point of view. More than just Olympic urbanism, it is time to imagine a shared Olympic urbanism for tomorrow.More reading

Read also

What lies ahead? 7 megatrends and their influence on construction, real estate and urban development

Article

20 minutes of reading

Energy

in partnership with

‘Paris at 50°C’: a fact-finding mission to prepare Paris for future heatwaves

Article

2 minutes of reading

What if your sites were supplied via rivers instead of roads?

Article

3 minutes of reading